The odour of my work is distinctively female

Let me introduce the french artist Florence-Marceau-Lafleur:

Florence answers to twelve questions about her work in the FEMALE GAZE.

(If you wish a German translation, please scroll down.)

Florence Marceau-Lafleur, Paris, 1988

lives and works in Haarlem, the Netherlands

1. What does the Female Gaze mean to you?

There are two responses that come to mind when I read your question. One of them is the counterpart of the ‚male gaze’, that is, an objectifying way of looking at women that deprives them of any agency. In this way, I understand the female gaze as a way of looking at women as peers/equals. The other response is more personal. I have noticed that many women, in particular fellow artists, have a specific relationship with touch and vision, as if they could touch with their eyes. I remember several conversations with women in which we evoked a form of scopophilia that would not stem from the distancing between the self and the other but from the perceived union of both. Endowing viewing with the same reciprocity as touch seems quite female-specific to me. But it is also a way to look beyond women/men relations and to build a relation to the world that also involves things and our own ‚thingness‘ within it.

2. Who influenced you and your artistic work?

Of course other artists, such as Femmy Otten, Thierry de Cordier, Tacita Dean, Rebecca Horn, Juul Kraijer, Martin Assig, and many nameless artists. Writers like Hervé Guibert, Virginia Woolf, Roland Barthes, Simone Weil, Emily Dickinson, Marguerite Duras, Catherine Millet, Francis Ponge. Researchers like Vinciane Despret, Jack Hartnell, or Philippe Descola. Often I am interested in people exploring non-modern relationships between body and world.

3. Can the Female Gaze also be taken by a man?

If we understand it as a way of looking at women as peers/equals, yes, I think it is possible – yet rare. If we understand the female gaze in a more ‘tactile’ way, I never discussed this topic with men, while I often did with women. Perhaps men do, but discussing this with a woman might be transgressive. From his writings, Maurice Merleau-Ponty seemed to experience this reciprocal, almost tactile way of gazing at the world. Conversely, I observe the harshness of the objectifying gaze in women too – at times, I can recognise it in myself.

4. Could your (artistic) work also be done by a man?

No, I don’t think so. Virginia Woolf wrote that you should not think about your own sex while making art, but that, without thinking about it, something of your sex comes into your work, something hardly perceptible, like an odour. The odour of my work is distinctively female.

5. What would be the first thing you would do as a chancellor? Which law would you enact?

I think it is extremely important to dispose of one’s own life and body, and I am concerned about the current reactionary trend. Inscribing the right to abortion in the constitution would seem wise to me. The same goes for euthanasia.

6. How do you experience the topic of family planning as a female artist?

In the Netherlands, where I live, there is an increasing focus on the possibility for women to combine their artistic work and motherhood, but I have never had any desire to have a child myself. It is very important, as a female artist, to create a context in which you can find something – something that surprises you. This can include children or not. Motherhood can fuel one’s artistic practice, and in recent years, I have seen impressive works made by women about motherly love. It broadens my perspective because it is not an experience of life I have, but I can relate to their experience of total love and cosmic belonging. At the same time, it should not become a new norm or a form of pressure. I think it is important to respect the choice of each individual female artist.

7. Do men and women react differently to your art? If so, how?

Although my work is never properly sexual, there is a carnal aspect to it. This sometimes complicates the way it is received, by men in particular. I remember using the word ‘my body’ at an exam at the academy, and a male teacher asked me whether I was aware of the erotic connotations that my phrasing was carrying. The term, and what it referred to, seemed completely natural to me. Of course, this points to the fact that women are still perceived as commodities. Because of this, some women see a transgression in my work that appears corrupt to them. But in general, women relate to my work more easily, probably because there are many experiences we share and because these experiences are rarely symbolised.

8. What we need to know about you…

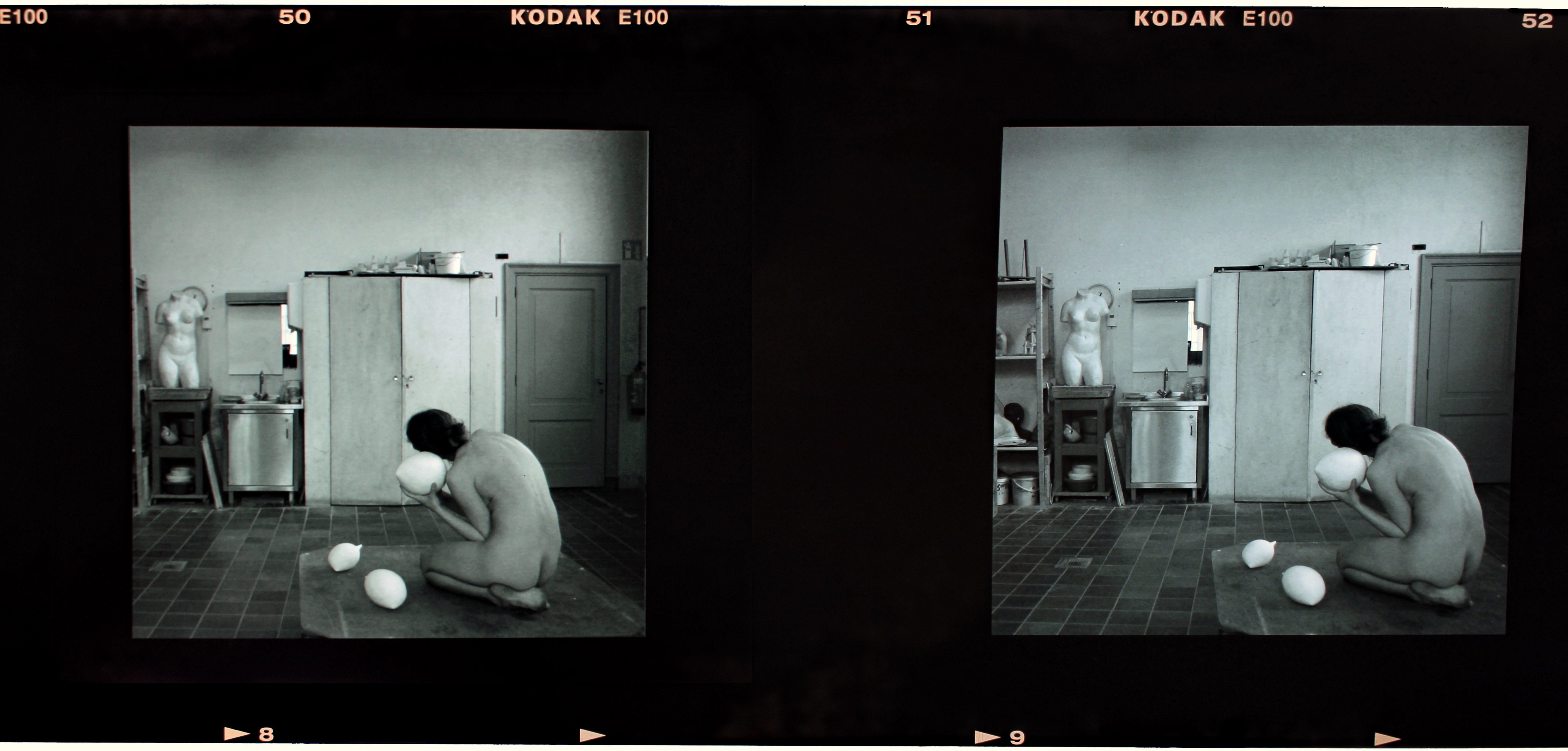

As an artist, I have always been inspired by fleeting moments of self-dissolution, especially those that are not traditionally represented in the arts (whether religious, psychedelic, or romantic). I have encountered an unusual form of contemplation as I started working as an art model to afford my studies in fine arts. To sit still for many hours a day, I triggered in myself a trance-like state, which made me experience my own body and the surroundings differently. As there was no contemplative imagery from this given place, I grew intrigued, and this became a source of inspiration in my work as an artist.

9. What does the concept of art include for you – what does it exclude?

It is not really a question I ask myself, precisely because I have often heard definitions that were primarily meant to exclude others. I prefer looking at things I feel sympathy with, at a certain moment and in a certain place. I call the translation of this sympathy ‘art’, but I don’t want to impose this definition on anyone else.

10. Are there gender-specific aspects in your art?

What inspires me most are moments of self-dissolution, so, when I am focused on my work, I am nothing and nobody. What I make is a resistance to identity, rather than an expression of it. But even then, I perceive the world through a specific perspective, which remains that of a woman.

11. Describe a work of yours that represents you as an artist…

It is not easy to single out one work: the relationships between them represent me.

12. Where does your artistic path start from and where does it lead?

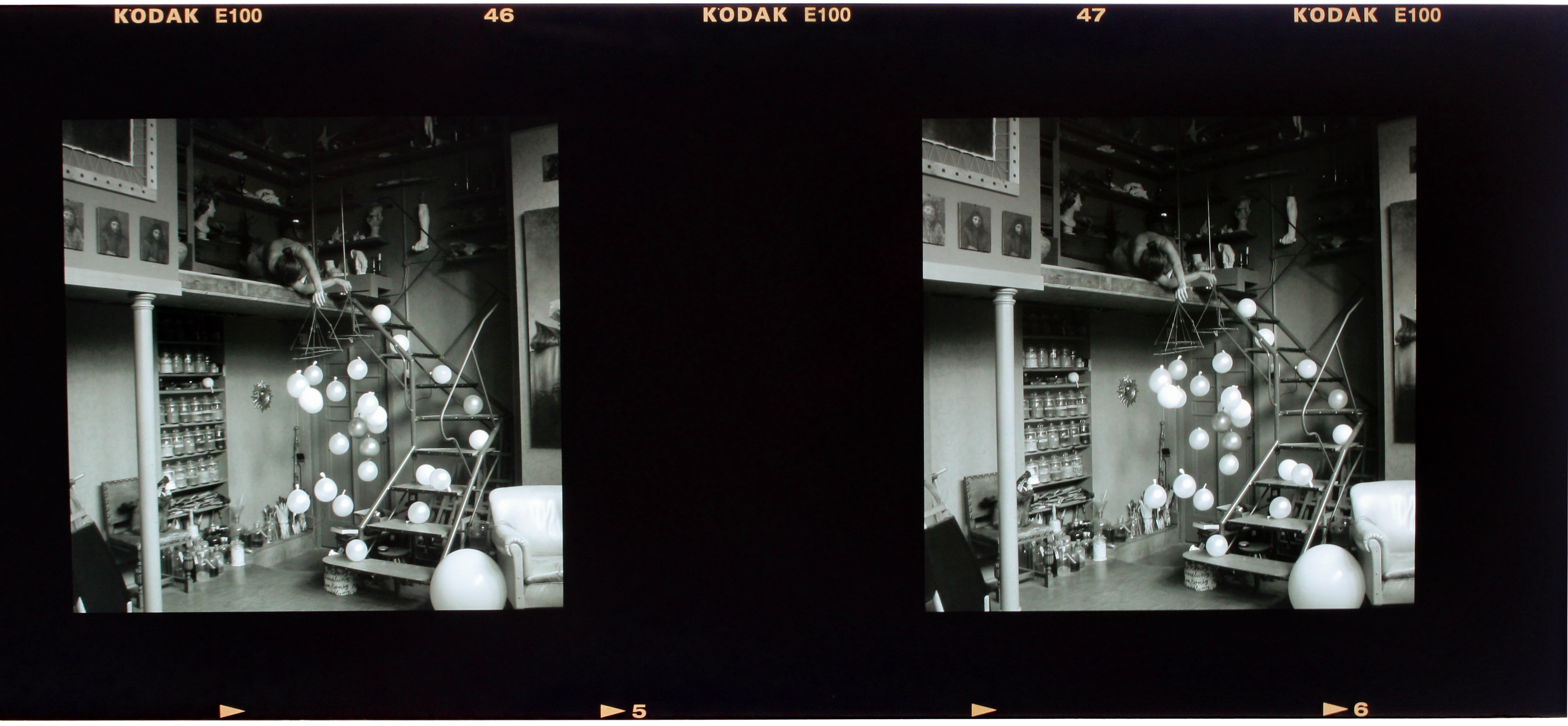

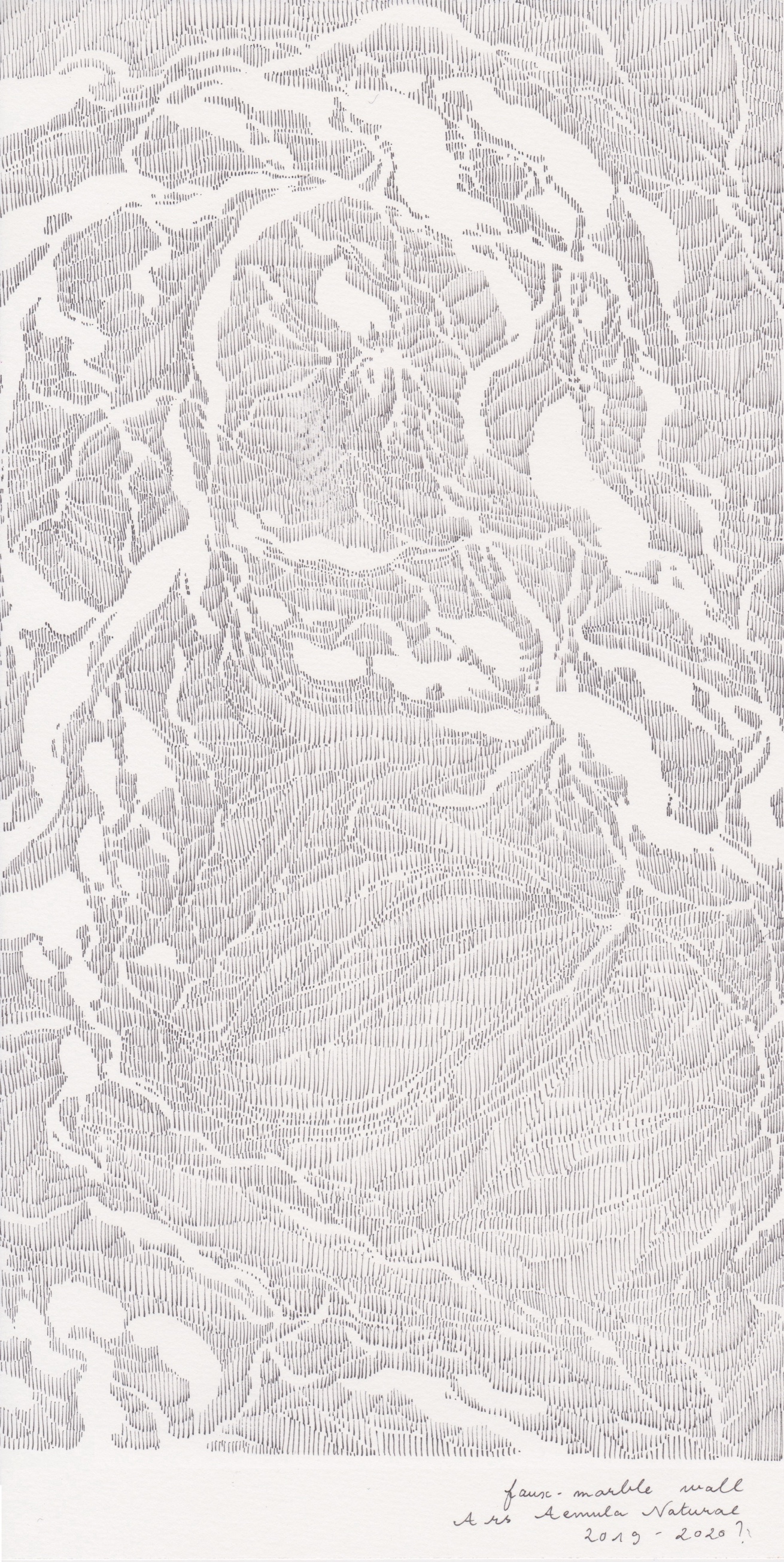

Modelling for art classes had a strong influence on my work at the beginning. There, I got interested in the way contemplation affected the perception of my own body in space. How many times do I need to breathe in to create my own volume? Can I use my own skin surface as an ideal format for two-dimensional works? I pondered these questions while posing, and implemented them in my studio.

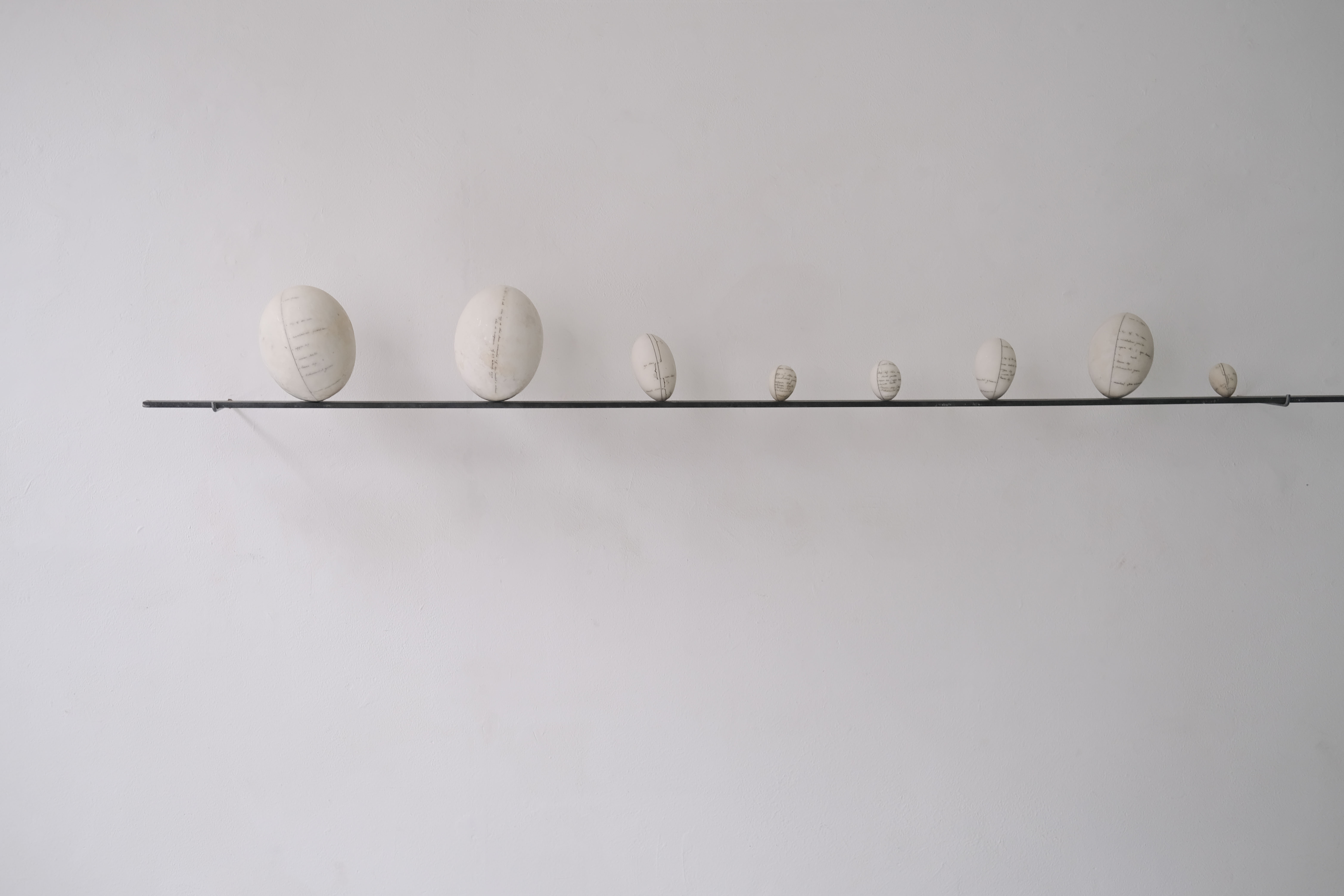

By now, I am interested in linking these personal experiences with a broader art-historical context, for example, the medieval concept of metric relics. The term refers to the body measurements of Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary. In the Christian tradition, Jesus and Mary’s bodies are assumed to be in heaven, and for this reason, there are hardly any bodily remains to be worshipped. To overcome this absence, Christians created abstract relics that represented the exact length of their bodies and body parts, sometimes associated with the measurements of their direct surroundings, such as their tombs, the cross, or the instruments of the Passion.

Discovering art historical articles on this topic enthused me, because the metric relics express a way of thinking that is similar to the one I had as a model. I am now working on small reliquaries whose insides are empty, but scaled to my own respiratory volumes. Self-proportioned books of hours are yet to come…

Merci Florence for partaking the FEMALE GAZE on your mind and work.

To find out more about Florence Marceau-Lafleur: Take a look on her Website.

And here comes the German translation:

1. Was bedeutet der weibliche Blick für dich?

Beim Lesen deiner Frage, kommen mir zwei Antworten in den Sinn. Eine davon ist das Gegenstück zum „männlichen Blick“, das heißt eine objektivierende Sichtweise auf Frauen, die ihnen jedes Alter entzieht. In diesem Sinne verstehe ich den weiblichen Blick als eine Möglichkeit, Frauen als Gleichgesinnte zu betrachten. Die andere Antwort ist persönlicher Natur. Mir ist aufgefallen, dass viele Frauen, insbesondere Künstlerkolleginnen, eine besondere Beziehung zur Berührung und zum Sehen haben, als ob sie mit ihren Augen berühren könnten. Ich erinnere mich an mehrere Gespräche mit Frauen, in denen wir eine Form der Skopophilie (Schaulust/Voyeurismus) hervorbeschworen, die nicht aus der Distanz zwischen dem Selbst und dem Anderen, sondern auf der wahrgenommenen Vereinigung beider resultiert. Das Betrachten der gleichen Gegenseitigkeit auszustatten wie die Berührung, scheint mir ziemlich frauenspezifisch. Aber es ist auch ein Weg, über die Beziehungen zwischen Frauen und Männern hinauszublicken und eine Beziehung zur Welt aufzubauen, die auch die Dinge und unser eigenes „Ding-Sein“ in ihr einschließt…